High on Hope - Acid House Documentary (Piers Sanderson Interview)

We spoke with Piers Sanderson, director of acid house doc High on Hope, as the film forms part of the programme of events at new Manchester club Underland.

Jimmy Coultas

Date published: 5th Feb 2014

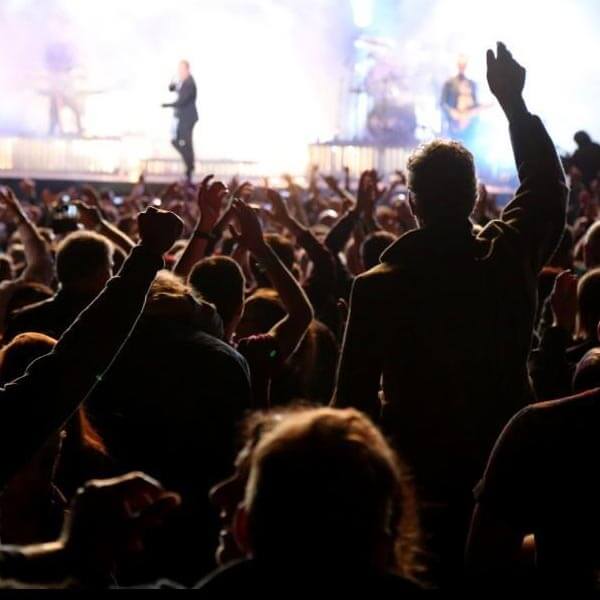

New club Underland recently opened in Manchester and on Saturday 8th February they've added a bold goal that runs a little off the page of the usual thrust of clubland with the start of a series of events called Sound & Motion. They've omitted to provide just DJs, instead allaying them with a documentary behind the clubbing movements they're seeking to celebrate at the start. First up is an acid house special featuring a DJ set from A Guy Called Gerald and the screening of the documentary High on Hope.

The film, which you can watch the trailer for above, seeks to tell the story of the working class involvement in the spreading of acid house in the North West of England, in particular Blackburn. Away from the oft publicised tales of the Hacidena this is a less romantic and well worn story of arguably the last truly era defining musical movement, and essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in the reasons we're all able to rave in 2014.

We caught up with the documentary's director Piers Sanderson, who got involved with acid house round about the same time as a particularly famous DJ in the late eighties (find out who below). With the film still slightly shy of reaching it's funding targets to be released (head here to learn how you can play your part), Piers delivered the reasons behind why the film and the event is worth your attention.

Hi Piers. For some of our readers who might not know you, can you give us a bit of background on yourself and you role in both music and film?

Hi Jimmy thanks for your interest in the film. In 1988 I had just finished my A levels at a technical college in North Wales and I was supposed to start university in September. However that summer also happened to be when acid house really took off. Having been just old enough to see punk (but too young to be a part of it) and hearing about the sixties from my mum, I knew that this was the scene my generation had been waiting for. It felt special, secret, ours, brand new. Uni was going to have to wait.

For the previous year, together with my mate from college, we had been putting on Chicago House parties (the term 'acid house' hadn't been coined yet). At the start of that summer we loaded up my VW Beetle and moved to Manchester. That was the start of 15 years of making a living out of dance music for me. And my mate, Sasha, well I am sure you know what he went on to achieve.

Around 10 years ago i started to feel restless and suspected that music wasn't my life's purpose - i was looking for a new challenge. Around this time i saw an amazing film at the cinema called 'Dark Days'. It was a documentary about homeless people that lived in the tunnels under New York. It was beautifully shot on black and white 16mm film and the music was by DJ Shadow. I hadn't realised documentaries could be so creative. I knew then what I wanted to do.

The first film i wanted to make was one that looked at why the early days of acid house had made such a big impression on those that experienced it. The Blackburn warehouse parties in my opinion summed up what was so special about that time. Also the experience of those who were behind it was a great way of showing societies reaction to a youth cult they didn't understand. I made a short version of the film and that got me into film school an ultimately an MA in documentary direction. I finally got to finish my education.

So what was the thinking behind High on Hope, and why did you feel it was better to focus on a more unfashionable aspect of the club culture than the usual tropes and stories such as Hacienda, Shoom etc?

I never went to Shoom but the Hacienda was the reason I discovered house music. Whilst it was an amazing club that shaped the scene I loved so much, it was still having to operate within the confines of the restrictive licensing laws of the 1980's.

The Blackburn parties were put on 'by the people for the people'. There was an ideology about them (before the gangsters took over and ruined it). It wasn't about making money, it was about creating a space where people could dance to the music of their choice, for as long as they wanted, wearing what they wanted. All things we take for granted now but had to be literally fought for 25 years ago.

The people who put them on every week went to such extreme lengths to evade the authorities and did the most unbelievable things to get the party off. Imagine trying to get 10,000 people into a different warehouse every week whilst the might of Her Majesties Constabulary are working full time to stop you.

There were police guarding every industrial estate in Lancashire, there were practically no mobile phones, no social media. It seems impossible on paper, yet a small group of friends pulled it off every week for 18 months and were only stopped when they were illegally held in Victorian prisons for months on end. Now that is a story!

On the night a Guy called Gerald is playing after your film is shown at Underland. How important was his role in shaping acid house for you?

He was a true pioneer of the music and he has managed to stay at the cutting edge his entire career. I remember the first time I heard 'Voodoo Ray' (below) played in the Hacienda. It blew me away. I wasn't usually one to go to the DJs and bother them, but that night i went straight to the booth and told Mike Pickering I thought the track was brilliant. He said the guy who made it is here, you can tell him yourself. I remember Gerald being really modest and quite surprised at my enthusiasm.

What first attracted you to electronic music?

It depends what you mean by electronic music? The big synth bands of the early 80's you could say were electronic but iI didn't really connect with them. However the more psychedelic bands using synthesisers in the 70's, like Pink Floyd, connected with me from a really early age. When Electro came along in the mid 80's I knew it was getting close to what I was into, but still didn't feel like 'my' music.

I started going to the Hacienda in 1986 and at that time the music was really eclectic there. It would move through the night in small generic sections. Half an hour of hip hop, half an hour of funk and soul etc. Then one week i heard 'Love Can't Turn Around' by Farley Jackmaster Funk and Darell Pandy. That four four kick drum got inside my chest. I was like 'what was that? I want more!'

The next week there were three house records together, the next week half an hour of house. I knew I had found my music. Within a few weeks acid house was born! For the next 15 years I found a way to make a living from that music. Not as a way to capitalise on it, but as a way to maintain a lifestyle.

What DJs were big for you at the time?

Me, Sasha and two other friends shared a house in Salford so going out was usually centred around where Sasha was playing if he was playing somewhere. In those early days the Hac wouldn't book Sasha for some reason but we still went there a lot. John Da Silva, Steve Williams and Laurent Garnier were always brilliant, as were Parks and Pickering.The southern DJ's rarely came North then and vica versa so i only really knew of the Manchester based ones.

Did you feel that it was a life changing movement at the time?

Absolutely! That is why I wanted to make the film. Ask anyone who was a part of it if it was life changing and I guarantee they will say yes. Ask them why and they will struggle to put it into words. That is why i wanted to explore this time of our lives some more.

Do you think any of the beliefs of the time have been lost over the years?

It was all very utopian, possibly unrealistically so, for a very brief time, and then we all lost sight of the dream. However I do believe that there is an acid house mentality that has survived. You see it in the choices that people made subsequently. Through traveling and enjoying new places and being in the company of people you would never have dreamed of being with before this scene came along your eyes were opened to other choices, other possibilities.

We also challenged authority and in some ways we won. The licensing laws changed. More freedom came in to night spaces. There was more expectancy of difference. These are not exclusively down to acid house but I believe they are some its legacies.

And finally, what else lies in the future for you form a film perspective?

Here is a Skiddle exclusive for you Jimmy - I am currently working on the follow up to High On Hope. I will not say too much but it does cover the subsequent period - from when acid house went from a small British underground movement to become a global phenomenon.

High on Hope still needs to raise money to license the music for a full release - head here for more information.

To get tickets to see the film and A Guy Called Gerald at Underland on Saturday 8th February head here.

Tickets are no longer available for this event

Read more news