The Hacienda Hangover: Why is Manchester so obsessed with the 80s and 90s?

Sick of the black and yellow stripes? We take a look at Manchester’s cultural legacy of the 80s and 90s - what keeps dragging us back to it?

Gabriel Arnold

Last updated: 17th Nov 2025

We guarantee you’ve heard it all before. Black and yellow stripes adorning nightclub pillars, an era defined by illicit substances, boundary-pushing electronica, and the last bus stop for bone-shattering rock and roll. A powerhouse of music, culture, sport, and industry, Manchester does it differently, was created on the seventh day, and so on and so on.

When it comes to depictions and views of this city, we too often lean into the brief pocket of time where the likes of 808 State and A Guy Called Gerald occupied the speakers of any half-decent dancing den. But why? Manchester is a city that’s experiencing considerable growth and investment this century, with new districts, venues, and cultural hubs sprouting up every other year.

Oli Wilson certainly has an answer. The son of the city’s famed promoter and presenter, Tony Wilson, Oli followed in his father’s footsteps during his teen years, promoting his first love, drum and bass. “I actually went to uni not to study, but to promote - and go to - drum and bass nights every week. I’ve been a promoter independently and for other organisations throughout my 20s and 30s.” Oli’s recent work has seen him start Beyond the Music, a music conference and festival that tackles some of the industry’s biggest existential crises and questions, and launch the new music magazine platform Soledad.

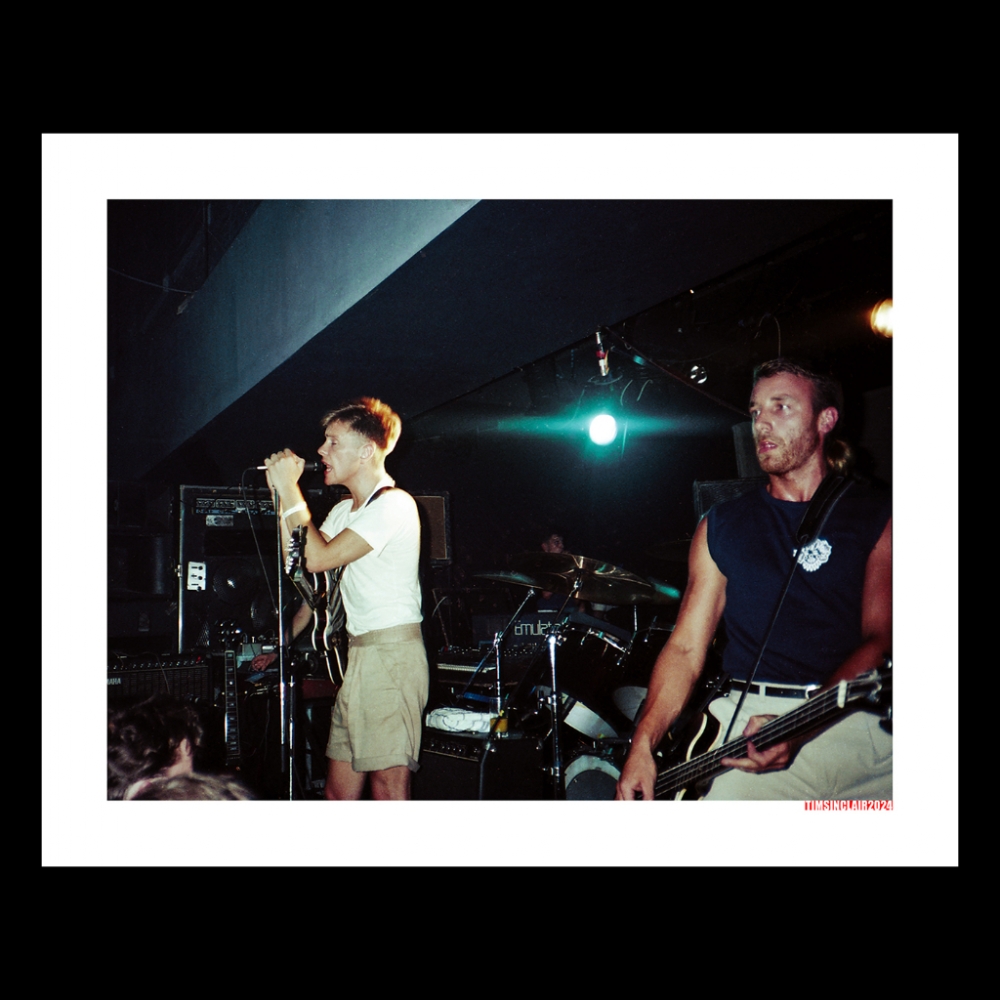

New Order at The Hacienda, 1983

Photo credit: Tim Sinclair / Manchester Digital Music Archive

Unsurprisingly, Oli is no stranger to the enduring cultural shadow the Hacienda has left on the city, having grown up amid the burgeoning acid house movement brewing inside the club walls. “It’s probably the best way to grow up as a kid,” Oli remembers, “Not a lot of people got to witness the acid house revolution, where my dad used to take me into the Hacienda. What an experience that was. You can’t quite figure it out as a child. Even the music doesn’t make sense when you’re a kid.”

Oli saw the confusing yet exciting world of acid house flourish throughout his childhood, and grew up rubbing shoulders with city stalwarts New Order and Happy Mondays, even going on tour with them, and spending time in Granada Studios, where his father worked as a TV presenter. “It was just the most amazing playground. I’m glad I saw the community that existed at the time, which was one big family with no gatekeepers; it was a very supportive scene, a very permissive and inclusive one.” For him, the scene was a mosaic of creativity, with everyone having their individual part. “Everyone could get involved, which, you know, is kind of different these days, isn’t it?”

Former resident DJ Jon Dasilva, when chatting to him about the club’s mythologised image last year, agreed: “For the time, it was quite radical in its ideas, it was one of the few clubs that had its own nights, and you couldn’t hire the Hacienda and do your own club nights. I think it’s been sanitised to an extent, despite the films and whatever, it was a lot more visceral, exciting, and left-field musically than it’s ever been portrayed.”

In Oli’s eyes, things have changed, and with the cultural revolution came a commercial, capitalist cycle. “It’s not so easy to get involved in the music industry these days, and I feel like there are a lot of people who should be working in it who aren’t. I’m happy to have seen the 80s and 90s because I think it’s really relevant again today, and everything comes in cycles. After the 80s and the 90s, the city has been used as an investment vehicle, and the culture has been used as a shopfront, so it’s become very wearing in the city because of the way that legacy has been used over the last 10 to 15 years.”

"The culture has been used as a shopfront, so it’s become very wearing in the city because of the way that legacy has been used over the last 10 to 15 years.”

Can the continued use of Manchester’s cultural legacy be derived solely from consumerism? Surprisingly, for someone who witnessed the glory days, Oli finds less and less time for its depictions. The famed phrase “This is Manchester, we do things differently here”, attributed to his father, never left his lips. “It just shows how much this city is using its cultural heritage to sell things to the point where they’re actually fabricating it, because they use a quote that my dad never said, and that kind of parallels with the Hacienda as well. I think everybody is sick of black and yellow stripes.”

That’s not to say that Manchester has nothing new to hang its hat on. “There’s so much good stuff going on here, so many brilliant promoters, artists, DJs, clubs, and entrepreneurs doing all sorts of stuff in the music industry,” Oli said, with his focus being on revitalising an ever-shrinking music press. “I was at the MTV Europe Music Awards, and it was a rolling your eyes moment when the black and yellow stripes came up; it takes the light off of what’s going on here at the moment. It’s a column inch taken away from new music and new scenes.”

Resurrecting a struggling music press and promoting the city’s new talents are two of the main aims of Oli’s new platform, Soledad, a music magazine aiming to usher in a new era for music journalism. The impetus for Soledad was a chance encounter with a local producer, who’d risen from bedroom DJ to selling out shows internationally and working with Grammy-winning artists, who couldn’t land a prop in Manchester. Oli went to work and tried to drum up some local press, but to no avail. “That’s one of the main reasons why I did it, because there needs to be something supporting artists here in Manchester that’s regular. There are a lot of great publications and zines out there, and there needs to be something weekly that platforms them.” Artists and producers aren’t the only ones struggling either, as Oli’s experience working in music saw him bump into plenty of music journalists having to work other day jobs to support themselves. “We think that there should be a platform to create an ecosystem that pays people to write while giving new artists a platform.”

Back in the 80s and 90s, print media had a far tighter stranglehold over the music industry, with magazines like NME having a big sway on where public opinion leaned, although, Oli remarked, his father’s famed company, Factory Records, didn’t always see eye to eye with the magazine. “Before the internet, the only way you could get your playlists and (event) listings was through these kinds of magazines,” Oli recalled, “They were really crucial to gaining information for any music fan.” In addition to alternative publications like NME and Melody Maker, dance mags and fanzines have been mainstays since the 80s in supporting the scene. “There’s not much difference between what we’re doing with Soledad. It’s been done for many years like with City Life, which was an independent publication that started in the 80s and ran through the 90s in Manchester. We need local sources of information at the moment, because there’s so much out there, so why not have something bringing it all together, making sense of it?”

A declining print media and a lack of opportunities for local artists and journalists may explain why the 80s and 90s still hold such a vital place in the city’s culture, but its prevalence never fails to divide opinion. For those like Oli, the sentiment ‘nostalgia is a disease’ comes to mind. Freelance journalist Davey Brett concurred in 2022, when he penned an opinion piece for Confidentials asking everyone to “stop shagging the Hacienda”, as he compared the BBC documentary The Hacienda - The Club That Shook Britain to a Soccer AM sketch, which skimmed over the venue’s history of inclusivity and its contributions to uplifting black and LGBTQ+ artists. “(Nostalgia) is definitely something that we’ve caught here in the city in recent times,” Oli added, “but ultimately the new era of Manchester has already started, and it will find the Hacienda and the 90s completely irrelevant. I bet they never even think about it.”

"The new era of Manchester has already started, and it will find the Hacienda and the 90s completely irrelevant. I bet they never even think about it."

Advertising certainly plays its part as well. Creative Review looked at Manchester United’s kit reveal ad last year, which featured Barry Keoghan surrounded by 90s iconography, “Even in advertising now, the 90s nostalgia is so prevalent and widespread,” Oli said when I asked about the uptick in 90s nostalgia within the advertising space. “It’s definitely from people growing up and getting older. When I was younger, the 70s and 80s were big. The 90s are in vogue at the moment with people who were not even born then, and I suppose it's because it was a great era and it's probably the last great era in British pop music, at least that we've had up until now.”

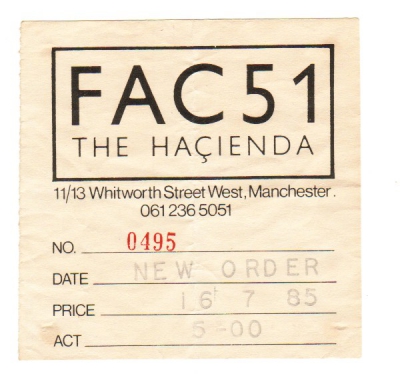

Hacienda Classical keeps the name alive in the events space, even with decades passing by since the space was converted into city-centre apartments. “The rise of Hacienda Classics brings strings to it, so it’s got an establishment vibe to the whole thing,” Dasilva said, “It was really important culturally for not only the North West, but the country in itself because I know for a fact there were promoters on my guest list that came, saw, went home and delivered their own club nights, whether in Nottingham, Birmingham, Glasgow or wherever.”

Hacienda flyer, 16th July 1985

Photo credit: Manchester Digital Music Archive

With the new era of the city needing more love, where do we need to look? “We’ve got a lot of history since the Hacienda that’s just as laudable, from Electric Chair through to Warehouse Project,” Dasilva argued. Nowadays, the city isn’t short of iconic venues, as Oli points out. “The notable ones are White Hotel, The DBA, Hidden, The Loft, I think it’s brilliant what the guys are doing down at Progress Centre and Joshua Brooks are focusing more on their resident DJs, which is a great direction to go in.”

We’ve been no strangers to covering 90s nostalgia, especially in the wake of Oasis reuniting to applause and acclaim, and recently took a glance at what the current wave of nostalgia tells us about the modern world. It remains to be seen what the true meaning behind Manchester’s obsession with a bygone era is, whether it’s soulless marketing clinging to the scraps of rave iconography or if it’s the result of yearning for better times. As the city moves further away from the mills and gasometers of its past and continues to embrace glass skyscrapers and urban sprawls, it can’t hurt to reminisce on a time when the North West bore kinetic chasms of creativity and was able to thrive. Maybe we’re just focusing on the wrong details.

Follow us on Instagram, TikTok, Threads, Facebook, and YouTube for the latest music and events content.

Read more news